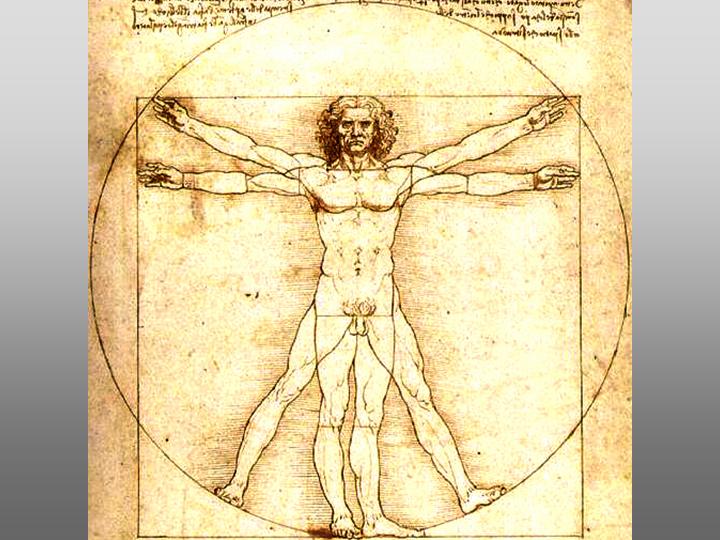

Vitruvian man

Leonardo was born on Apr. 15, 1452, near the town of Vinci, not far from Florence. He was the illegitimate son of a Florentine notary, Piero da Vinci, and a young woman named Caterina. His artistic talent must have revealed itself early, for he was soon apprenticed (c. 1469) to Andrea Verrocchio, a leading Renaissance master. In this versatile Florentine workshop, where he remained until at least 1476, Leonardo acquired a variety of skills. He entered the painters' guild in 1472, and his earliest extant works date from this time. In 1478 he was commissioned to paint an altarpiece for the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. Three years later he undertook to paint the Adoration of the Magi for the monastery of San Donato a Scopeto. This project was interrupted when Leonardo left Florence for Milan about 1482. Leonardo worked for Duke Lodovico Sforza in Milan for nearly 18 years. Although active as court artist, painting portraits, designing festivals, and projecting a colossal equestrian monument in sculpture to the duke's father, Leonardo also became deeply interested in nonartistic matters during this period. He applied his growing knowledge of mechanics to his duties as a civil and military engineer; in addition, he took up scientific fields as diverse as anatomy, biology, mathematics, and physics. These activities, however, did not prevent him from completing his single most important painting, The Last Supper.

With the fall (1499) of Milan to the French, Leonardo left that city to seek employment elsewhere: he went first to Mantua and Venice, but by April 1500 he was back in Florence. His stay there was interrupted by time spent working in central Italy as a mapmaker and military engineer for Cesare Borgia. Again in Florence in 1503, Leonardo undertook several highly significant artistic projects, including the Battle of Anghiari mural for the council chamber of the Town Hall, the portrait of Mona Lisa, and the lost Leda and the Swan.

Leonardo returned to Milan in June 1506, called there to work for the new French government. Except for a brief stay in Florence (1507-08), he remained in Milan for 7 years. The artistic project on which he focused at this time was the equestrian monument to Gian Giacomo Trivulzio, which, like the Sforza monument earlier, was never completed. Meanwhile, Leonardo's scientific research began to dominate his other activities, so much so that his artistic gifts were directed toward scientific illustration; through drawing, he sought to convey his understanding of the structure of things. In 1513 he accompanied Pope Leo X's brother, Giuliano de'Medici, to Rome, where he stayed for 3 years, increasingly absorbed in theoretical research. In 1516-17, Leonardo left Italy forever to become architectural advisor to King Francis I of France, who greatly admired him. Leonardo died at the age of 67 on May 2, 1519, at Cloux, near Amboise, France.

Other, slightly later works, such as the so-called Benois Madonna (c. 1478-80; The Hermitage, St. Petersburg) and the unfinished Saint Jerome (c. 1480; Vatican Gallery), already show two hallmarks of Leonardo's mature style: contrapposto, or twisting movement; and chiaroscuro, or emphatic modeling in light and shade. The unfinished Adoration of the Magi (1481-82; Uffizi) is the most important of all the early paintings. In it, Leonardo displays for the first time his method of organizing figures into a pyramid shape, so that interest is focused on the principal subject--in this case, the child held by his mother and adored by the three kings and their retinue.

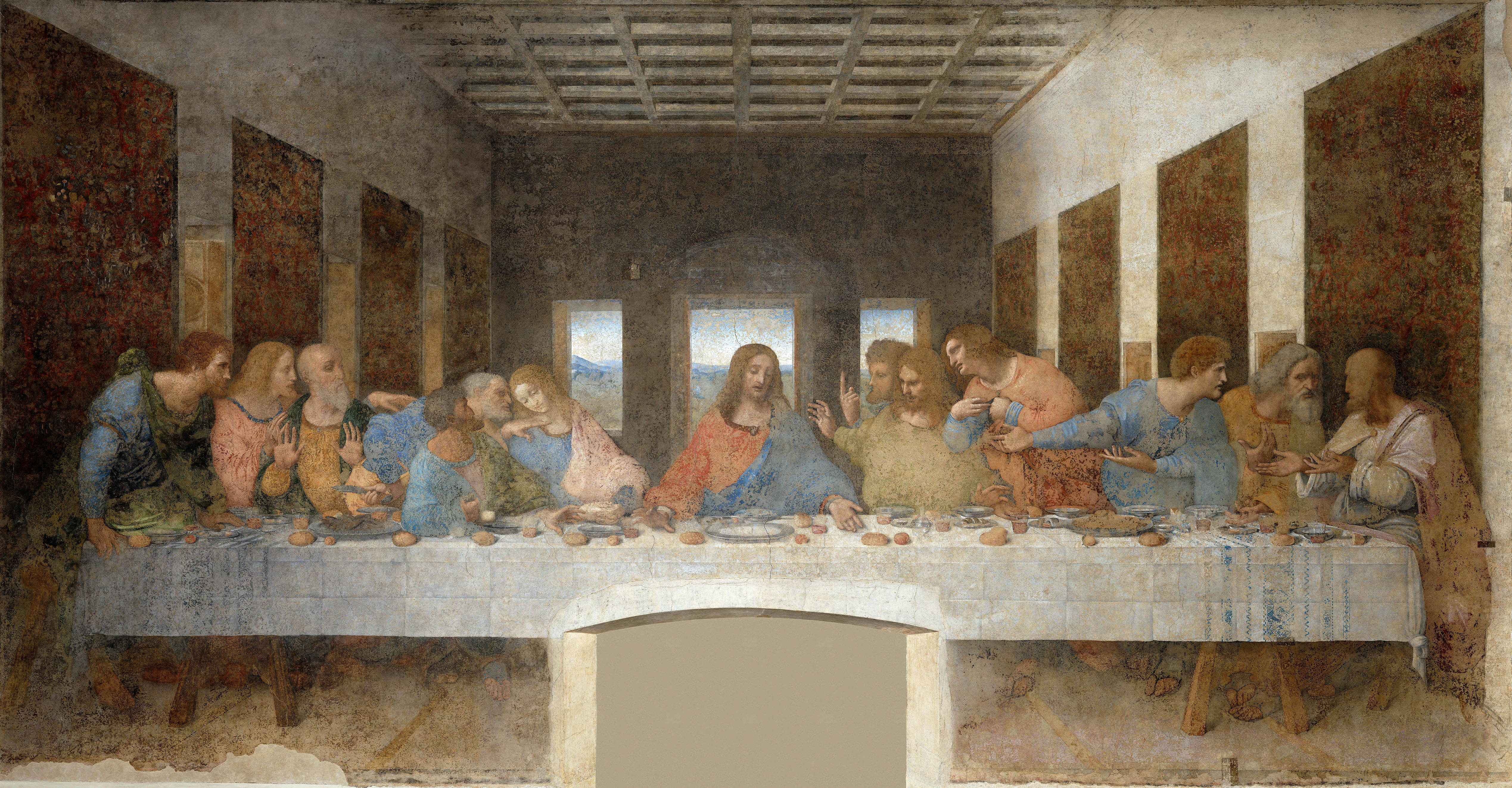

In 1483, soon after he arrived in Milan, Leonardo was asked to paint the Madonna of the Rocks. This altarpiece exists in two nearly identical versions, one (1483-85), entirely by Leonardo, in the Louvre, Paris, and the other (begun 1490s; finished 1506-08) in the National Gallery, London. Both versions depict a supposed meeting of the Christ Child and the infant Saint John. The figures, again grouped in a pyramid, are glimpsed in a dimly lit grotto setting of rocks and water that gives the work its name. Not long afterward, Leonardo painted a portrait of Duke Lodovico's favorite, Cecilia Gallerani, probably the charming Lady with the Ermine (c. 1485-90; Czartoryski Gallery, Krakow, Poland). Another portrait dating from this time is the unidentified Musician (c. 1490; Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, Milan). In the great The Last Supper (42 x 910 cm/13 ft 10 in x 29 ft 7 1/2 in), completed in 1495-98 for the refectory of the ducal church of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, Leonardo portrayed the apostles' reactions to Christ's startling announcement that one of them would betray him. Unfortunately, Leonardo experimented with a new fresco technique that was to show signs of decay as early as 1517. After repeated attempts at restoration, the mural survives only as an impressive ruin.

When he returned to Florence in 1500, Leonardo took up the theme of the Madonna and Child with Saint Anne. He had already produced a splendid full-scale preparatory drawing (c. 1498; National Gallery, London); he now treated the subject in a painting (begun c. 1501; Louvre). We know from Leonardo's recently discovered Madrid notebooks that he began to execute the ferocious Battle of Anghiari for the Great Hall of the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence on June 6, 1505. As a result of faulty technique the mural deteriorated almost at once, and Leonardo abandoned it; knowledge of this work comes from Leonardo's preparatory sketches and from several copies. The mysterious, evocative portrait Mona Lisa (begun 1503; Louvre), probably the most famous painting in the world, dates from this period, as does Saint John the Baptist (begun c. 1503-05; Louvre).

The Last Supper

Leonardo's art and science are not separate, then, as was once believed, but belong to the same lifelong pursuit of knowledge. His paintings, drawings, and manuscripts show that he was the foremost creative mind of his time.

No comments:

Post a Comment